Art Artist's Statements Artistic Motivations: Art Philosophy Artist's Statement

by David Jay Spyker

leave a comment

Artist’s Statements, Part 2

You might like to start with Part 1

I recently wrote about my initial reluctance toward having any artist’s statement for my show (Memory, Essence, Mystery). As I thought more and more about it, and began to write, the words also came more easily. I ended up with, in addition to the statement in the catalog, three other statements spaced around the exhibition room. They really helped to tie everything together, and make that personal written connection between the art and the people looking at it.

Each of the three wall cards dealt with an aspect from the show title, though they were not specifically labelled as such:

Memory

There is a relationship to personal experience in my art. What may seem like an “ordinary” landscape or shore scene actually has personal significance to me; it has memory tied to it. Sometimes, there is a reflection of that in the title of a painting. You may not know the exact connection at a glance, but it’s there.

When we interact with people, or engage with places, they become more important to us. We are woven into their fabric, and they into ours. It’s not the place that is significant, it’s what we did or felt while we were there. Each of us also has those special possessions, which mean a lot to us because of the memories surrounding them.

Personal memories and experiences are frequently expressed in my work. I’m trying to talk about them, and my thoughts and feelings that encompass them; I’m just using a visual language to do it.

Essence

There can be a lot of artistic editing that happens when I’m working out a painting based on life. I may alter colors and tones, modify some forms, or even leave out or add certain elements.

For me, there is more leeway when dealing with a landscape than, say, a portrait of a person or a bird – there you want to get the depiction of form and the inner character right.

Getting every branch on a distant tree to match what I see in the landscape isn’t so important, but finding the character of the landscape is. I may change the lighting in a scene so it works toward the emotion of the whole picture.

What matters most is that the picture express how I feel about the subject. I want the deeper character, or essence of it to come through; you should really feel something when you look at it.

Of course, some pieces are complete fabrications, and then any “rules” really fly out the window. It becomes about imagination and creating something that has the emotion I’m after, and says what I want to say.

Mystery

Like Andrew Wyeth’s quietly disturbing, highly personal images or the silent, still moment of a Vermeer, I want to capture a feeling of strange wonder that there may be something deeper and mysterious going on in a painting.

Even when it seems ordinary at first glance, I am so often trying to find something subtle – the lingering of something left unspoken or a kind of breathlessness – a stillness.

Whatever it is, if I can find that deeper emotion and work it into the picture, then I know I’ve done something right. I’m on the right track.

Art Artistic Motivations: Art Philosophy Artist's Statement

by David Jay Spyker

leave a comment

Artist’s Statements, Part 1

Let’s start by saying that as I have matured over the years, I have also become less of a fan of artist’s statements – you know, those paragraphs you see in a show catalog or hanging in the exhibition that explain who the artist is, why they do what they do, and what their work means.

Too often they read like pseudo-sophisticated bullshit that’s tailored to self-stroke the artist’s own ego, to display an intelligence and mastery of the complexities of language, or are designed to appeal to some sort of elite art world ideal.

As I considered what to say about my own most recent show (Memory, Essence, Mystery), I went through a range of emotions on the subject. I considered not even having a written statement in favor of letting the paintings and drawings simply speak for themselves, but eventually decided against it because it was still important to make that connection with the viewer about the work.

When I create art, it’s like writing in a visual language; not everyone thinks that way – a great many people think in words, and there is a communication gap there. Coming up with something to say about my work – to bridge that gap and forge a stronger connection – became important again.

It was also important to speak from the heart because that is the origin of my art; I didn’t want to intellectualize it, and risk losing that chance to speak about my work in a way that would click with people on an emotional level.

The best course for me was to write more like I might speak, to honestly transcribe the words I could hear in my mind without dressing them up in fancy clothing. This is what ended up being printed in the show catalog:

My paintings always have some kind of personal story or significance. There has to be that connection, whether it’s something coming from deep within, an inspiration tied to someone in my life, or memorable experiences that have shaped the way I feel and think about the world around me. Most often it’s all of those things. I feel very fortunate in that regard – to be able to weave those threads together in my art, and have that sort of personal connection on all those levels, because putting that down in a visible, tangible form is how I talk about life. In the end, it’s about personality, what’s in your heart, what you love – you know, that’s what makes your art great, that’s what gives it feeling. Without all of that coming through, what’s the point?

Work from the heart – write from the heart.

Timelessness in Art

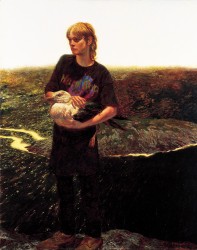

You can often overhear interesting things in art museums and galleries. On the last day of “The Wyeths: America’s Artists” at the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts, a man standing one painting to our left said with a semi-sour look, “The mullet kind of dates it”; he was looking at Jamie Wyeth’s “Portrait of Orca Bates”, and I think he mostly missed the point – but I’ll get to that.

Timelessness is one of those art terms that, if you frequent artsy circles, you will regularly hear thrown around. You will most often hear it used in a context of either praise or derision; it’s one of those art terms. Andrew Wyeth is known to have said that he liked painting nudes because of the timeless quality of the picture; I think maybe depicting a nude in front of some sort of amorphous background is the only way a figurative painting might be considered timeless (in the sense of the art term, at least), and even then, hair styles may be a giveaway to the time period.

Because we only have the personal experience of our own time, I think it is much easier to see images from the past as having a timeless quality. What we’re really seeing is unfamiliarity, out-of-our-own-timeness, not timelessness. Old stuff – frilly clothing, long bygone hair styles, antique personal accouterments, horses, ragged wooden shacks – always has a way of seeming classical, timeless. Maybe in a few generations, a mullet, a gold stud earring, battered work boots, and a Hard Rock Cafe t-shirt will be classical too; we just can’t see it right now. Personally, I don’t really care, it’s a beautifully expressive painting.

Maybe the real questions are: Does it matter? Are we getting the point?

I don’t think timelessness really matters.

First, pure timelessness is very rare.

Second, our enjoyment and understanding of a painting shouldn’t be swayed by critical art-world terminology.

Third, art is better understood when taken in the context of the artist’s time period and personality, and the Wyeths are no exception to this. Andrew and Jamie are known for distilling the essence of their experiences, surroundings, and imaginations in their paintings. It is this very observation and recording of their intimate universe coupled with a willingness to externalize their hearts and minds that makes their art so great – so full of meaning and emotion. When we begin to engage with all the possible stories behind their images, when we begin to understand and have a feeling for the artist’s intent, they only become deeper.